[wp_ad_camp_1]

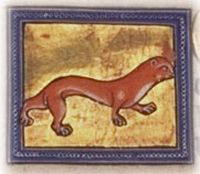

Aberdeen Bestiary, c 1200 AD

Medieval bestiaries were based on early Greek and Latin texts and were lavishly illustrated, the most well known of one being The Aberdeen Bestiary.

Medieval bestiaries were based on early Greek and Latin texts and were lavishly illustrated, the most well known of one being The Aberdeen Bestiary.

This Bestiary was written in the North Midlands of England around 1200 AD and consists of 104 folios.

The picture of the weasel is Folio 23v, with the description:

The cat, a catcher of mice, mice; the weasel, who hunts snakes and gives birth through its ear or mouth.

The folio on the weasel gives us one of the earliest insights to an animal which could well have been the polecat/ferret, as well as keeping alive the weird impression, found both in the Epistle of Barnabas and The Metamorphoses, about weasels conceiving through the mouth.

“It hunts snakes and mice. There are two kinds of weasel. One, of very different size from the other, lives in the forest. The Greeks call these ictidas; the other roams around in houses. Some say that weasels conceive through the ear and give birth through the mouth; others say, on the contrary, that they conceive through the mouth and give birth through the ear; it is said, also, that they are skilled in healing, so that if by chance their young are killed, and their parents succeed in finding them, they can bring their offspring back to life.

“Weasels signify the not inconsiderable number of people who listen willingly enough to the seed of the divine word but, caught up in their love of wordly things, ignore it and take no account of what they have heard.”

According to the medieval bestiaries, a basilisk was usually described as a crested snake, or occasionally a cock with a snake’s tail.

Its Latin name is Regulus, and its considered the king of the serpents because its Greek name, basiliscus, means little king.

Its odor was said to kill snakes, fire from the basilisk’s mouth was supposed to kill birds while its glance was enough to kill a man! Yet another way it killed was by hissing.

Basilisks were hatched from a cock’s egg (!) and only a weasel could kill it.

The picture, taken from Folio 66r of the Aberdeen Bestiary, shows a weasel attacking the basilisk.

© University of Aberdeen, Images used with permission

Queen Mary’s Psalter, 14th Century AD

A Psalter is a collection of psalms for devotional or liturgical use during the Middle Ages.

Many psalters had fabulous illustrations and Queen Mary’s Psalter actually has drawings of weasels which were shown to “conceive through the mouth and give birth through the ear“.

This is obviously a hangover from Greek mythology days, like what happened to Galanthis.

The Bard and his Weasels, 1564-1616 AD

William Shakespeare, who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, was around during the reigns of both Elizabeth I and James I, and was a favorite of both monarchs.

William Shakespeare, who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, was around during the reigns of both Elizabeth I and James I, and was a favorite of both monarchs.

He is without a doubt the most famous literary figure of that time and several of his plays have references to mustelids sprinkled through them!

You’ll find in a part of Henry V there is a reference to “the weasel Scot” who comes sneaking and sucks her princely eggs!

You’ll find that old Will enjoys talking about weasels sucking eggs because in As You Like It, a chap called Jaques reckons he “… can suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs“.

In Cymbeline, women are said to be “… as quarrelous as the weasel …“. Hrumph! If Shakespeare were around now, I would certainly take issue with him about that statement. Quarrelous, indeed!!

Then in Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark looks at a cloud and thinks it looks like a weasel (very fertile imagination, Hamlet old boy).

And last but not least, in The First Part of Henry IV, Lady P reckons that “A weasel hath not such a deal of spleen …“.

Hmmm, you reckon it mean that the weasel doesn’t vent its spleen but it’s just a sweet little pussycat?

So with all the descriptions in Shakespeare’s plays, we must assume that the medieval English folk had quite a lot to do with weasels, polecats and ferrets in their day.

Well, that’s my take on it anyhow and I’m sticking to it! Heh heh.

The illustration below shows more of how the weasel was thought of during the Middle Ages.

[wp_ad_camp_3]